By Guy J. Sagi

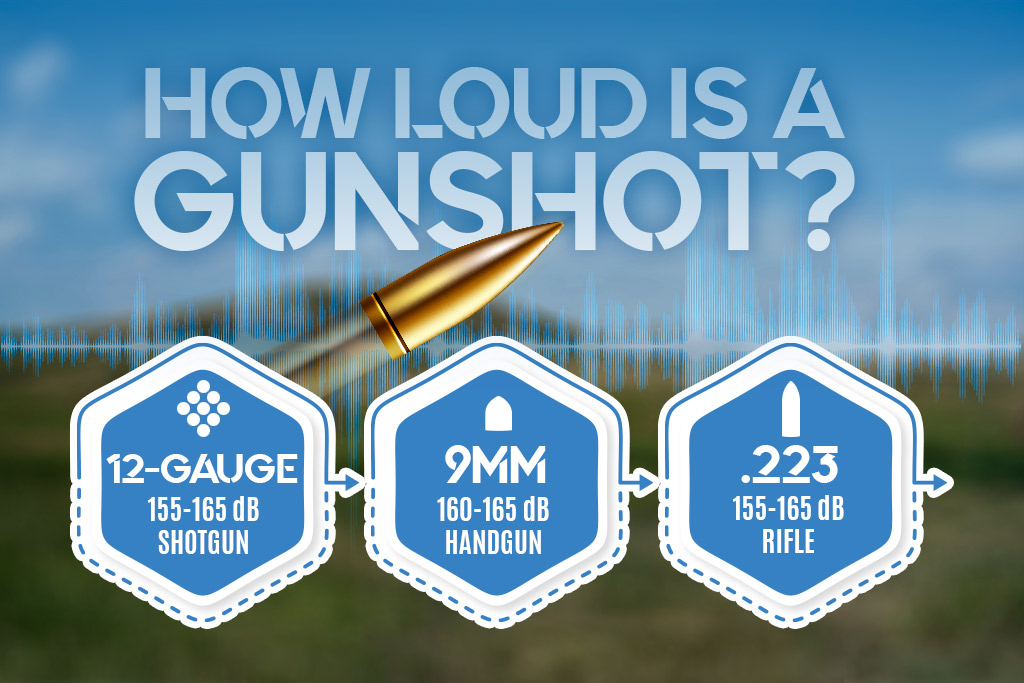

How loud a gunshot is depends on the firearm, but it’s usually pretty loud. Send a single round downrange without hearing protection, and permanent damage can result—even complete loss of hearing. You can eliminate the risk by wearing foamies, quality earmuffs, or modern electronic versions with suitable decibel-reduction ratings. Every experienced shooter knows it’s a basic safety requirement when firing. Recent testing conducted by Widener’s indicates it’s even more important than many realize.

It’s not just the gun and cartridge that affect how much sound pressure reaches your ears. Business is booming at indoor ranges. Their walls and roof do a good job of preventing the noise from annoying homeowner association activists. The tradeoff is that nearly all of it remains inside, turning up the volume on the firing line.

Big-bore rifles are common today, and so are muzzle brakes that make even traditionally tame rifles and pistols bark with high-caliber authority. The variables are a compelling argument that shooters should own and religiously use hearing protection that exceeds minimum standards. Doing so is especially vital for those times when someone in the lane next to you uses a surprisingly loud firearm.

Results from our testing indicate other factors may be at work. It could be the current enthusiasm for upgrading guns, particularly ARs. Cartridges have also evolved, and manufacturers continue to improve firearm designs. Is that relegating some widely circulated noise-pressure figures to mere baseline status?

Eye-Opening Tests: Just How Loud is a Gunshot, Anyway?

How loud is a gunshot? A 12-Gauge shotgun blast is usually around 155-165 dB.

Call it professional curiosity, but we decided to measure peak gunshot sound levels from four different firearms. We used a distance-calibrated Larson Davis Spartan 821Sound Level Meter. Results recorded maximum sound pressure in L-APK—frequencies in the human hearing range—and L-ZPK, a peak low frequency, and raw peak pressure measurement. The instrument’s ability to dial into the range most critical for hearing provides an uncluttered glimpse of the risk of shooting without hearing protection.

| Caliber | L-APK | Average | L-ZPK | Average |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| .22LR | 143.2, 143.5, 143.3 | 143.33 dBA | 143.9, 144.2, 143.8 | 143.97 dBZ |

| 9x19mm | 156.2, 155.1, 155.8 | 155.7 dBA | 156.7, 155.9, 156.5 | 156.37 dBZ |

| 12 Gauge | 155.3, 155.5, 155.3 | 155.37 dBA | 156.8, 156.9, 156.6 | 156.77 dBZ |

| .223 Rem | 164.5, 165.3, 165.6 | 165.13 dBA | 165.4, 166.4, 166.5 | 166.10 dBZ |

We placed the sound-level tester 1 meter to the left of the gun barrel and elevated it 1.6 meters above ground. The microphone angled up at 90 degrees relative to the barrel. We conducted the test in an open field with no structures or surfaces for audio reflection.

This is a noise-limiting setup rarely encountered by shooters. Even under those conditions, the rifle firing .22 LR always exceeded the Occupational Safety and Health Administration’s (OSHA) maximum safe decibel (dB) exposure of 140.

How Loud a Gunshot is Compared to Common Sounds

The noise level ratings of sounds we commonly experience help put the results into perspective. Normal conversation is 60 to 70 dB, and lawnmowers measure between 80 and 100. Rock concerts score anywhere from 80 to 120, and the synchronized cheers, screams, and taunts at NFL games are 90 to 135 dB (depending on score and halftime show).

| Common Sounds | Noise Level | VS Gunshot |

|---|---|---|

| Normal Conversation | 60-70 dB | BB Gun |

| Lawnmower | 80-100 dB | .177 Pellet Gun |

| Rock Concert | 80-120 dB | (Suppressed) 22LR Handgun |

| Sporting Event | 90-135 dB | (Suppressed) 9mm Handgun |

| Emergency Siren | 110-129 dB | (Suppressed) AR-15 Rifle |

| Fireworks | 110-140 dB | (Suppressed) .308 Rifle |

| Jet Engine | 140-150 dB | .22LR Pistol/Rifle |

First-responder sirens sound at 110 to 129 dB. Fireworks can reach the 140 dB threshold, and jet engines fly above it at somewhere between 140 and 150. Of course, all of these noises can be amplified, depending on their surroundings and your proximity to them.

The Surprise

How loud is a gunshot? An AR-15 rifle is usually around 155-165 dB.

Sound pressure levels produced by three of the four guns tested were close to widely cited figures. However, one demonstrated how much gun setups, perhaps even loads, can lead to a surprising increase.

In 2014, the Council for Accreditation in Occupational Hearing Conservation compiled a list of sound pressures generated when firing different cartridges. It reported that a 5.56 NATO/.223 Rem. cartridge produced 158.9 dB. Other reputable sources today put the figure at 155.5.

Our results, at minimum, were 7 dB higher. It’s no surprise to see variation between AR-15s. They are, after all, available in hundreds of configurations direct from factories, and it’s the most modified platform today. Whether a byproduct of muzzle device, barrel length, or the cartridge, the difference is significant. Let’s put it into perspective with a quick look at how sound pressure is assigned a decibel value.

The Count

The decibel scale begins at 0, total silence, and the number increases as sound rises. It does so in logarithmic fashion, however.

When the number increases by a single digit, it indicates 10X more sound pressure. In our case, the bump of 7 dB translates to a 70x louder gun report.

Anyone who’s experienced the thump of a .50 BMG or .338 Lapua Mag. going off nearby is probably skeptical about whether all that energy is really aimed at your hearing. It turns out that nearly all of it is.

Audible Sound’s Bullseye

Our results include the L-APK value, which measures only sound pressure within the human hearing range. That runs roughly from 16 to 16,000 hertz (Hz) for the average person in their thirties. (Younger people generally hear higher frequencies, and the ability to do so tends to decline with age.)

In musical terms, deep bass starts at 16 Hz. Cymbals ring at somewhere around 16,000 Hz, and lyrics are between 2,000 and 8,200 Hz. Conversation during intermission takes place between 80 and 255 Hz.

All the L-APK values from our test are above the established permanent hearing damage levels. The American Speech-Language-Hearing Association (ASHA) website warns, “It’s crucial to understand that exposure to noise greater than 140 dBP [decibel peak pressure] can permanently damage hearing, even from a single occurrence.”

That means anyone nearby who wasn’t wearing suitable protection during our experiment was at serious risk of losing some or all hearing. And this is from the diminutive .22 rimfire. That’s how loud a gunshot is as a baseline.

Standards published by OSHA clearly warn, “Exposure to impulsive or impact noise should not exceed 140 dB peak sound pressure level.” The dangers of impact noise are not the same as the sounds we routinely experience at home or work. Both can cause damage, although the former does so quickly.

Noise Types

Amanda Edens, Acting Director of the Directorate of Enforcement Programs at OSHA, explains on her organization’s website.

“Impulsive noise, which includes impact and impulse noise, is a rapid rise in sound pressure that typically lasts less than one second. Impulsive noise is generally more hazardous than continuous noise, and it has a synergistic effect when combined with continuous noise exposure. Some exposures can have peak levels above 170 decibels or dB (e.g., flash-bangs, large caliber firearms, breaching operations).” – Amanda Edens, OSHA

Continuous noise takes longer, but it can be just as damaging to your hearing. OSHA standards require that if an employee, on any 8-hour workday, is subjected to an average of 85 dB per hour, the company must implement a hearing-conservation program. Construction companies, airports, and many major industries adhere to these guidelines.

Accurately measuring gunshot sound pressure is more challenging than monitoring the din on a factory floor, however. Today’s high-tech meters do yeoman’s work, but the variables make apples-to-apples comparison difficult. Mother Nature’s a minor player on that culprit list.

Environment: Affects how Loud a Gunshot Sounds

Sound moves through the air as waves. Temperature, humidity, and even barometric pressure affect it. On hot days, for example, it travels faster. Conversely, it can carry further on cold days, particularly those experiencing a temperature inversion.

Noise is louder when the humidity is high. Low clouds can reverberate a firearm’s report. Noise is heard best at sea level, not at high altitude, where the air grows scarce.

It’s interesting stuff, and mathematically a bit simpler when sound pressure is measured with a distance-calibrated meter.

Surroundings

Surfaces can reverberate sound—like the roof and walls of an indoor shooting range. Consider the corrugated tin roofs and concrete shooting benches common at outdoor sites. There, the volume goes up a notch or two.

Shoot from the ground or low in the prone position, and the effect is similar. Exterior factors contribute, but we eliminated them. So what’s the primary suspect in the 70X case?

Firearm & Ammo

How loud is a gunshot? A gunshot from a 9mm handgun is usually around 160-165 dB.

Enthusiasts prefer flat trajectories. Cartridge manufacturers respond with hotter loads and sleek bullet profiles that produce that familiar “crack” as they break the sound barrier faster than their predecessors.

Short barrels are louder than long ones. Muzzle brakes turn up the volume, despite decreasing the amount of sound pressure that reaches the person behind the trigger. Flash hiders also alter the report.

More than likely, all of the above contributed to our .223 Remington findings. Which one is the primary suspect? We may never know. However, the lesson is still an important one. Anyone who shoots that gun without hearing protection rated at 25 dB is at risk of suffering hearing damage.

Other Factors in How Loud a Gunshot Is

Sometimes you need to double up—foamies in the ear, earmuffs on top. The practice is common because sound pressure increases as gun caliber climbs. For example, several studies concur that .30-06 Springfield-chambered rifles produce sound pressure that averages around 170 dB. That’s nearly 35X louder than our tested .223 Rem. rifle and 30 dB higher than the unprotected damage threshold.

Sitting near or behind that gun at an indoor range, or under a metal or wood roof, increases your sound pressure exposure. A muzzle brake, hot load, or short barrel adds to the effect. Suddenly, 30 dB-rated hearing protection is no longer sufficient. That’s when it is wise to put two barriers between your hearing and the gun’s report.

Double the Items, Double the Protection? Not Quite

Don’t make the mistake of simply summing up the ratings and thinking that’s the total effectiveness. The experts have invented a shorthand solution for arriving at that figure without using calculus. Simply add five to whichever hearing protection rating is highest between the two. For example, if your earmuffs are rated at 15 dB and your earplugs at 30, you’re effectively blocking 35 dB of sound pressure when doubled up, not 45.

Ways to Reduce How Loud a Gunshot Is

Subsonic loads eliminate the nasty “crack” sound as the bullet breaks the sound barrier. Remember, though, some cartridges like the .45 ACP never leave a gun that fast in the first place.

Suppressors are another alternative. Despite Hollywood’s portrayal, they do not silence gunshots. Like hearing protection, they reduce sound pressure, nothing more. Manufacturers routinely publish their dB rating, which is an important consideration when used on higher-caliber rifles like those common for big game hunting.

Do not assume a suppressor alone will drop sound pressure below the safe threshold. Do the math (simple subtraction in this case) to determine if you still need hearing protection.

Remember, 140 dB is the level at which hearing damage occurs. Ringing in your ears after one unprotected shot may end the next day, but the damage is cumulative and irreversible. That’s just one sign that it’s past time to upgrade your hearing protection or religiously double up.

Why Obey the Safety Rules?

A 2024 paper issued by the National Hearing Conservation Association agrees that damage occurs when the 140 dB line is met. It adds, “Firearm users tend to have high-frequency permanent hearing loss, which means that they may have trouble hearing speech sounds like ‘s,’ ‘th,’ or ‘f’ and other high-pitched sounds.”

Gunfire is about the worst thing you can do to your unprotected ears … A single blast can cause lasting hearing loss and tinnitus. Once the damage is done, there’s no taking it back.”

— Susan E. Terry, Au.D.

The effect isn’t equally distributed—at least at first. “The loss is often worse in the ear closer to the firearm muzzle,” it states. “This means that, when shooting rifles and shotguns, right-handed shooters typically suffer more hearing loss in the left ear. In contrast, left-handed shooters typically suffer more hearing loss in the right ear.”

Can You Hear Me Now?

Bring your ears to the gun range: Hearing loss can begin to happen around noises as loud as 140 dB.

The long-term impacts of hearing loss are serious. They include an increased risk of cognitive decline, depression, isolation from loved ones, dementia, and more. Every gun’s impulse sound, regardless of chambering or caliber, can do permanent damage instantly unless you’re wearing hearing protection. We now know how loud a gunshot is: way louder than anyone thought.

Along with eye protection, hearing protection is mandatory when you’re at a shooting range—and there are no exceptions.