By Guy J. Sagi

California Sen. Kevin de Leon was the first to publicly use the term “ghost gun” during a press conference in 2014. GhostGuns.com opened in July of the same year and began offering home-assembly firearm kits and other gear. The publicity that followed the website’s launch—and attempt to trademark the name—heightened awareness of the designation.

The freshly-minted label became a media darling and quickly gained traction with elected officials. Its widespread use continues, despite a shape-shifting definition that often mutates in political winds and creeps onto firearms owned by law-abiding citizens. Those blurred borders can’t help but leave the average enthusiast wondering: What is a ghost gun, really?

Some think any homemade firearm fits the definition. Others consider commercially available kits completed by an owner or cleverly home-brewed to be one. Another camp claims any firearm lacking a serial number is a genuine ghost gun. The latter belief is where we’ll start.

History Of Firearm Serial Numbers

A Glock serial number on a handgun frame (Left), and a Sig Sauer serial number on a fire control device (Right).

Tens of thousands of firearms manufactured by major companies and still in use today do not wear a serial number. That federally mandated industry standard did not become law until the Gun Control Act of 1968. A grandfather clause in the legislation makes older models that lack this identifier legal to own, shoot, sell, or pass on as a family heirloom.

Many enthusiasts proudly cling to the serial-number-free firearms their parents or grandparents owned. Tens of thousands remain fully functional and make regular appearances on opening day or at the range. Due to disrepair, others continue to serve with distinction on a mantle. They are an integral part of a family’s heritage and a fond connection to a distant past. For that reason, discussions get heated and opinions sharply divided at any attempt to lump all firearms that lack a unique identification mark into the ghost gun category.

Pre-1968 Firearms

Admittedly, some manufacturers started putting serial numbers on their guns long before 1968. Quality control was a primary motivation in many cases. Companies like Winchester established a rudimentary ID system in 1866, although some records subsequently fell victim to fire and mishandling.

Colt’s Manufacturing started putting numbers on guns in 1849, although its first method proved somewhat confusing. Browning began doing so in 1903. Readers eager to determine the age of one of their guns, at least the older ones wearing serial numbers, will find this NRA Museum web page a good resource.

The list doesn’t include every legendary manufacturer, however. Some didn’t start serializing until 1968 or slightly before—modifying a manufacturing process isn’t free, after all. Also missing are brands manufactured by some of the industry’s finest but sold under different labels. Retail goliath Sears and Roebuck offered Ted Williams firearms. Wards Western Field guns sold at Montgomery Ward, Western Auto offered Revelations, and J.C. Penney handled Glenfields. To say tens of thousands of the budget-friendly department store models went home and are still in use is an understatement. Not all of them wear serial numbers.

I have my father’s bolt-action 12-gauge, magazine-fed Western Field shotgun–and that’s no typo, by the way. I also have the single-shot, break-action Steven’s shotgun with which he took his first rabbit. Also in my possession is his single-shot, bolt-action .22 Remington TargetMaster. This I reserve for those occasions when a family member shows up bragging about their new ultra-accurate rimfire. Two are wall hangers, the other a tack driver, respectively. None have serial numbers.

There’s nothing spooky, new, or frightening about the lack of serialization in pre-1968 firearms. However, the ghost gun discussion gets needlessly murkier with the specter of DIY versions.

Homemade History

When Polymer80 started in 2013, they only produced DIY 80-percent handgun kits. The new PFC9 model is now a complete, serialized handgun.

Homemade firearms are nothing new in the United States. In fact, it borders on American tradition. In 1774, only a few months after Boston Harbor was the scene of a now-famous tea party, British troops began forcibly searching homes for guns and confiscating them. At a time when revolutionary storm clouds were gathering on the horizon, the British intended to leave unruly colonists defenseless.

Once the crown was content with Bean Town’s disarmament, a contingent of Red Coats marched toward Massachusetts. On July 29, 1775—after colonists refused to surrender their firearms at Lexington—the first shots of the Revolutionary War rang out.

The only armories were well-guarded by British troops. The American firearm inventory was not enough to threaten, much less defeat, what was then the mightiest Army on earth. To supplement what remained in revolutionary hands, shade-tree gunsmiths cobbled together enough raw materials to begin producing guns. Their contribution was a big one during our war for independence.

Government Suppression Of Home Smithing

The success of those firearms fueled a DIY passion among many enthusiasts, who continued the homebrew pursuit legally, largely unnoticed, for nearly 200 years. After 1934, they had to secure a tax stamp to make anything included in that year’s National Firearm Act (NFA) that passed—suppressors, machine guns, short-barreled rifles, etc. Still, there was no shortage of people who continued making their own and offering them for sale.

Four years later, the federal government passed a law making a license mandatory for anyone making and selling guns across state lines or internationally. Despite that limitation, some DIY makers found it a solid side hustle. A few even relied on it as a primary source of income for the next 30 years.

Gun Control and FFLs

All serialized gun sales must pass through a licensed FFL, the buyer must complete a form 4473 and pass a federal background check before being approved.

It was so popular that, by the 1960s, the Gun Control Act of 1968 addressed the pursuit. The legislation established today’s now-familiar retailer Federal Firearms License (FFL) system. It also required a license before manufacturing and selling guns, regardless of volume, location, or destination. Those made at home remained legal as long as they were for personal use and not for transfer or sale.

It did little to dampen the enthusiasm for making a functioning firearm with your own two hands, though. The number of modern sporting rifle lower receivers with serial numbers that sell each year underscores that fact.

The passion for that pursuit didn’t earn much public notice until sometime in the 1990s when a big surplus of unfinished AK parts came ashore. Kalashnikov fans rejoiced at the newfound supply.

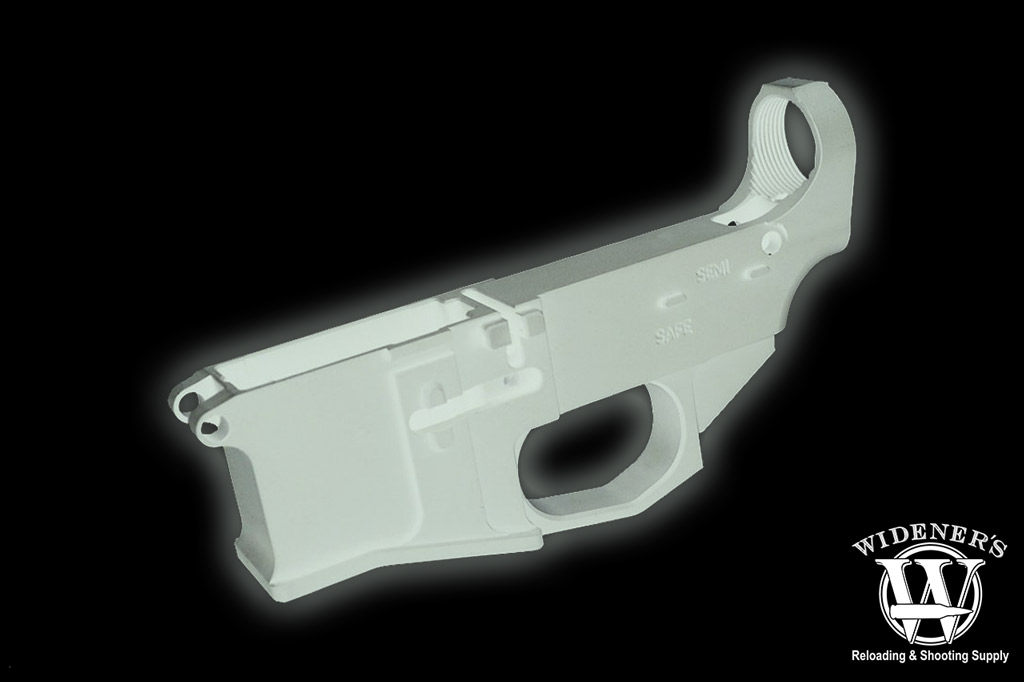

80 Percent Lowers

Boo! A spooky 80 percent lower that legally isn’t a gun, at least not according to the ATF’s own guidelines.

Those parts were far from complete and fell under the ATF’s 80 percent guideline that states, “Receiver blanks that do not meet the definition of a ‘firearm’ are not subject to regulation under the Gun Control Act (GCA). ATF has long held that items such as receiver blanks, ‘castings’ or ‘machined bodies’ in which the fire-control cavity area is completely solid and un-machined have not reached the ‘stage of manufacture’ which would result in the classification of a firearm according to the GCA [Gun Control Act].”

Enthusiasts gobbled them up. They milled, ground, and filed to create personal-use, serial number-free guns. Other 80 percent firearm receivers rose in prominence around the same time, particularly those for AR-15s. Business boomed for the firms offering them.

Working a metal blank isn’t for the faint-hearted, though. Aluminum and steel don’t tap and polish themselves, and few own an expensive lathe or know someone who does. Despite those challenges, diehards got the job done. Then, a new and gentler material appeared on the horizon.

Polymer Power

Polymer-framed, modular, and striker-fired handguns have been around for decades. Working this material is more DIY-friendly than wrestling with today’s Sumo-strength alloys. Polymer80—established in 2013—was among the first to introduce 80-percent complete polymer lowers. Like the metal lowers mentioned above, the ATF did not consider them firearms, which meant they wore no serial numbers.

That same year, the first 3D-printed polymer gun was introduced chambered for use with .380 ACP ammo single-shot pistol. The appearance of plans on the Internet sparked legal actions and debates that still rage.

The controversy fueled an already simmering political debate on 80 percent lowers. Bring either up in a room full of strangers, and the crowd divides into warring camps. With no consensus on the horizon, that still leaves a nagging question.

What Is A Ghost Gun?

What is a ghost gun? Technically, it’s a gun without a serial number, but there’s (a lot) more to the story.

Finding a precise meaning for the term ghost gun is a phantom that still eludes even those with a long history of crafting ironclad definitions. Merriam-Webster claims it is “…a gun that lacks a serial number by which it can be identified and that is typically assembled by the user (as from purchased or homemade components).” This storied source erroneously includes those lawfully made years ago and still in possession of the hobbyist.

Many other inaccurate attempts highlight the public’s general lack of knowledge about firearms and the strict laws surrounding them. Some definitions conveniently overlook the same fact that Merriam-Webster does.

Odd, since the ATF’s Form 4473, released in December 2022, prescribes a PMF (Privately Manufactured Firearm) entry in the manufacturer’s field when an FFL receives one. Other sources forget serial numbers only became mandatory in 1968—and guns, unlike today’s appliances, last for a century or more with care. Many sources ignore both facts.

Then, really, what is a ghost gun? The answer is simple: it’s a weapon in the spirit of our nation’s independence, law, history, and even heritage. It’s a firearm that is either complete or the ATF deems more than 80 percent complete. It is manufactured specifically for sale or transfer purposes after 1968 without a serial number.

It addresses what law enforcement claims is a booming black market, keeps heirlooms in the family, and doesn’t infringe on the DIY chromosome so prevalent among firearm enthusiasts. It’s not tied to a specific material or subject to unforeseen challenges as technology advances.

There are, however, two problems with it. First, there’s the brevity of it. There’s not enough breathing room in that single sentence for pundits to exploit. Second, the practice is already illegal, so there’s no political gain in adopting it.